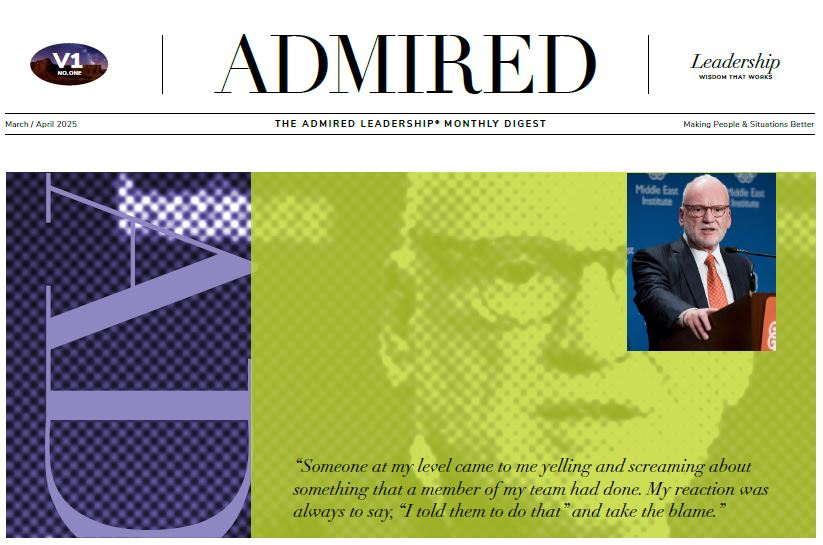

INTERVIEW WITH AN ADMIRED LEADER

From the Situation Room to the Boardroom: Richard Clarke on Leadership Under Pressure

Richard Clarke is an American national security expert and former government official who served across multiple U.S. administrations, including as National Coordinator for Security and Counter-terrorism. After leaving government service, he transitioned to the private sector, bringing his expertise to Boards and consulting roles. A celebrated author, Clarke continues to share his deep insights on precision performance, cybersecurity, and crisis management.

Excerpts from our discussion have been edited for length and clarity.

What facets of your childhood shaped your leadership skills?

I was fortunate enough to attend a great public school for grades 7-12, where there was an emphasis on public service and on public speaking, as well as a centuries-long list of famous alumni. Being the only child of parents who had been shaped by WWII was, no doubt, a part of what molded me, for better or worse.

What leaders with admirable behaviors have you worked with?

When I think of a leader, the skill that I think is so critical is communication and the ability to really connect with the audience. Bill Clinton had that ability better than anyone I’ve ever seen. He knew what he wanted to accomplish when he went into a room, he would completely transform himself to communicate a message designed and targeted for that audience.

But the key to public speaking as a leader is answering ‘why,’ which I think is the number one thing people forget. You’re not speaking because they want to hear you talk about whatever your issue is. If you’re motivating people to vote for you or you’re motivating your workforce to work—it’s all about the why. You have to say not why it’s important to you, but why it’s important to them. If you can, tell them why it’s about the greater good and beyond them.

Are there other leaders that come to mind that you especially admire?

Over the course of 25 years, I’ve really gotten to know the current president of the United Arab Emirates. He really focuses on communicating that he’s one of the people—that he knows what we’re going through, what our life is like, and there’s nothing that he would ask of us that he hasn’t or won’t do himself. He tries very hard to be a man of the people, and they understand that. That message gets across. It could be described as the servant leader model. It’s very compelling if you can make it believable, and for it to be believable, it has to be true.

What other thoughts do you have on the servant leader model?

It helps if you’ve done what you’re asking them to do. As an Assistant Secretary of State during the first Gulf War, I had 400 people in my organization. We had to work seven days a week for months on end. And nobody was doing anything less than 12-to-15-hour shifts. I think it helped that I was in that organization long enough that I literally worked my way up from the bottom, literally held every rank. I did all those jobs, and people knew it.

You can’t always do that. But you have to at least try to appreciate what every person’s job is like at their level, try to listen to them, to know what their problems are, to know what their challenges are, which means getting down to every level in the organization. ‘Management by walking around’ is the famous phrase.

You really need to get to every layer, every outpost of the organization, and take the time to listen to them and have them teach you what they do. That increases the credibility of a leader immensely.

How do you spot young talent? What are the things that you look for?

You have to get to know them. And one of the things I think a manager must do is find time—schedule it, because it’ll never happen otherwise. Find time to sit down one-on-one with as many people in the organization as you can. Ask them very simple questions like, “Where do you want to go? What’s your future in the next few years? Have you thought about how you’re going to get there? Now, what training do you need? What exposure do you need? What lateral movement do you need before you can move your way up?”

I tried to do that in the State Department when I ran the intelligence unit there. I tried to have a scheduled meeting once every six months—one-on-one with every one of my analysts, and there were a couple of hundred of them. It shows that you’re human and that you care about them. They understand that you’re interested in them. You want to hear their goals, their future, and what they’ve thought about.

And then I think if you find people who show some promise, throw them in the deep end of the pool. See if they drown. Some of them will, and you have to pull them out, and that’s fine. Then you have to reassure them that it was okay.

What other routines did you have to build teams, to keep teams on track?

What I tried to do every day in the White House was meet with my core team—about 10 people. They’d all get in sometime between 7:00 and 7:30 in the morning. I had a big conference table in my office. Every morning, they would have pastries and coffee on the table with all the intelligence reports that had come in overnight, and all the newspapers, and we would just all come in and sit around that table together for the first half hour.

When we found something that was interesting or actionable, or something that everybody else around the table needed to know, we’d call it out. So, we weren’t all reading the same things all the time. We were able to cover a lot more of the morning read because there were 10 of us breaking it up. We were sharing and beginning our morning together.

Then, at the end of the week, we’d all come together on a Friday afternoon, and turn that same office into a bar, into a cocktail lounge. Change the lighting, put on some music, put out some wine, and just have people wind down together. I think it’s very important that your team thinks of you as not someone who sucks up to bosses and kicks down to subordinates, but the other way around—someone who stands up to the bosses and supports the subordinates.

You’ve been around some high-performing teams. How did you handle it when one of your star players made a mistake?

I can think of half a dozen times when someone at my level came to me yelling and screaming about something that a member of my team had done. I learned this from a boss early on. My reaction was always to say, “I told them to do that” and take the blame. Then I would go to my team member and say, “What did you do?” I think it’s very important that the team members believe you have their back, even when they screw up. And everybody’s going to screw up. Your team members are going to screw up, and the key is to not have them go into a tailspin when that happens.

A Coast Guard officer came to me once who was working for me and said, “I have to quit.” And I said, “Well, why? Are you sick?” He said, “No. I just can’t do the job; it’s just too much.” Back to the throwing people in the deep end of the pool, I probably had thrown him in the deep end of the pool. And he was panicked, he was nervous. I said, “We’ve been trying to figure out what’s an appropriate portfolio for people. We’ve oversized your portfolio a little. Let’s take some of that off your plate, and just recognize that you’re really good, but we gave you too much.”

If people screw up, even if you have their back, they can go into a panic mode and they can spiral down. You really have to hold them up and say, “All right, you made a mistake. Everybody makes a mistake.”

You’ve worked in The Situation Room. How do you handle high pressure moments so that you have clear thinking and clear decision-making?

Don’t panic. It’s very important how you process information in a crisis. The other thing in crisis management is that everybody wants to talk at once, and people say things and they don’t get followed up. So, have a system where one person at a time is being called on to speak, and they have to speak very concisely. And you are literally tracking on a board all the actions that are coming up so that things don’t drop.