Key Quote:

“I don’t so much fear death as I do wasting life.” — Oliver Sacks

On Writing:

Oliver Sacks wrote constantly. Through weariness from bad health and restless nights, Hayes details Sacks’s obsession with writing.

“The most we can do is write – intelligently, creatively, critically, evocatively – about what it is like living in the world at this time” (p. 254).

Sacks enjoyed composing and sharing his thoughts with readers, but he didn’t seek to make things too easy on the reader. Hayes writes in his journal, “He insists on crossing out clauses suggested by a copy editor that define or explain an unusual word or term he has used: ‘Let them find out!’ he says, meaning – make the reader work a little. Go look it up in the dictionary, or go to the library” (p. 252)!

Even after a debilitating knee replacement, Sacks refused to quit writing, saying, “Writing is more important than pain” (p. 43).

After learning he had only months to live due to aggressive cancer, Sacks told Hayes that he was considering writing an essay on his diagnosis. At dinner the next evening, Sacks composed the entire piece while Hayes transcribed.

Sacks began, “‘I suppose I want to begin by saying that a month ago, I felt I was in good health. But…now my luck has run out…’” Hayes continues, “From there Oliver dictated the entire essay, nearly verbatim to the version that would eventually appear in the New York Times.” Hayes explains, “It was clear to me that he had been ‘writing’ this essay in his head over the past several days – and now, one perfectly formed paragraph after another spilled forth. It was astonishing” (pp. 244-245).

In the final days of his life, Hayes frequently found Sacks writing. Hayes explains in his journal, “All he needs is a pad and his fountain pen and a comfortable chair. Completely immersed, he whispers to himself as he writes – consciousness half a step ahead of the nib of his pen” (p. 273).

Sacks explained once, upon being found writing instead of resting, “I meant to stop but I couldn’t” (p. 273).

Insatiable Curiosity and Deliberate Practice

As a neurologist, writer, and piano player, he employed deliberate practice daily. He practiced incessantly, especially in unusual ways. Bill Hayes recounts Sacks studying during Hayes’ daily exercise: “I do fifty push-ups twice a day while [Oliver] sits at his desk and counts them out by naming the corresponding elements: ‘titanium, vanadium, chromium, manganese, iron, cobalt…’” (p. 263).

Sacks devoted his life to seeking knowledge, studying a very few topics extensively. Hayes wrote once Sacks quipped, “I specialize in a very large number of a very few things – magnifying glasses, spectacle cases, shoehorns, rubber bands…” (p. 99).

At the age of 75, Sacks had never been in love. His life was dedicated to his work: “Such a monk-like existence – devoted solely to work, reading, writing, and thinking – seemed at once awe-inspiring and inconceivable. He was without a doubt the most unusual person I had ever known” (p. 38).

Sacks once said, “Do you know why I love to read Nature and Science every week? Surprise – I always read something that surprises me” (p. 272).

On hearing his diagnosis of cancer with six to eighteen months to live, Sacks decided against harsh treatment just to prolong life by a bit. “I want to be able to write, think, read, swim, be with Billy, see friends, and maybe travel a bit, if possible” (p. 240).

Curiosity and intentional time spent with one’s work are the keys to discovering little details. Hayes writes, “No different from falling in love with a song, one may fall in love with a work of art and claim it as one’s own. Ownership does not come free. One must spend time with it; visit it at different times of the day or evening; and bring to it one’s full attention. The investment will be repaid as one discovers something new with each viewing – say, a detail in the background, a person nearly cropped from the picture frame, or a tiny patch of canvas left unpainted, deliberately so, one may assume,as if to remind you not to take all the painted parts for granted” (p. 229).

Thoughts on Thinking

Bill Hayes shares insight into the thoughts of Oliver Sacks and the child-like wonder that led to his profound musings.

Sacks was fascinated by the English language. He once wondered, “Are you conscious of your thoughts before language embodies them?” (p. 88).

Often triggered by a word or phrase, Sacks allowed his mind to wander and wonder: “Do you sometimes catch yourself thinking?” said Sacks in the car one day. “‘Those are special occasions,’ he went on, ‘when the mind takes off – and you can watch it. It’s largely autonomous, but autonomous on your behalf – in regard to problems, questions, and so on. These are creative flights… Flights: That’s a nice word” (p. 218).

“Oliver said that but was his favorite word, a kind of etymological flip of the coin, for it allowed consideration of both sides of an argument, a topic, as well as a kind of looking-at-the-bright-side that was as much part of his nature as his diffidence and indecisiveness” (p. 242).

Sacks said, “I want a flow of good thoughts and words as long as I’m alive” (p. 56).

Sacks on writing: “I say I love writing, but really it is thinking I love – that rush of thoughts – new connection in the brain being made. And it comes out of the blue.” He adds, “In such moments: I feel such love of the world, love of thinking” (p. 281).

On New York City

An insomniac in the city that never sleeps, Bill Hayes finds comfort in wandering the city and chance encounters with other sleepless city-dwellers. Hayes came to especially admire the New York City skyline at night after he first moved to the city.

Describing the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, Hayes writes, “Such a beautiful pair, so impeccably dressed, he in his boxy suit, every night a different hue, and she, an arm’s length away, in her filigreed skirt the color of the moon. I regarded them as an old married couple, calmly, unblinkingly, keeping watch over one of their newest sons” (p. 3).

Hayes feels a connection to the city because of his encounters with strangers, especially while on the subway, “marveling at the lottery logic that brings together a random sampling of humanity for one minute or two, testing us for kindness and civility. Is that not what civility is?” (p. 31).

“I’ve lived in New York long enough to understand why some people hate it here: the crowds, the noise, the traffic, the expense, the rents; the messed-up sidewalks and pothole-pocked streets; the weather that brings hurricanes named after girls that break your heart and take away everything. It requires a certain kind of unconditional love to love living here. But New York repays you in time in memorable encounters, at the very least” (p. 167).

We can learn from subways by what they do not do: “One may spend a lifetime looking back – whether regretfully or wistfully, with shame or fondness or sorrow – and thinking how, given the chance, things might have been done differently. But when you enter a subway car and the doors close, you have no choice but to give yourself over to where it is headed. The subway only goes one way: forward” (p. 32).

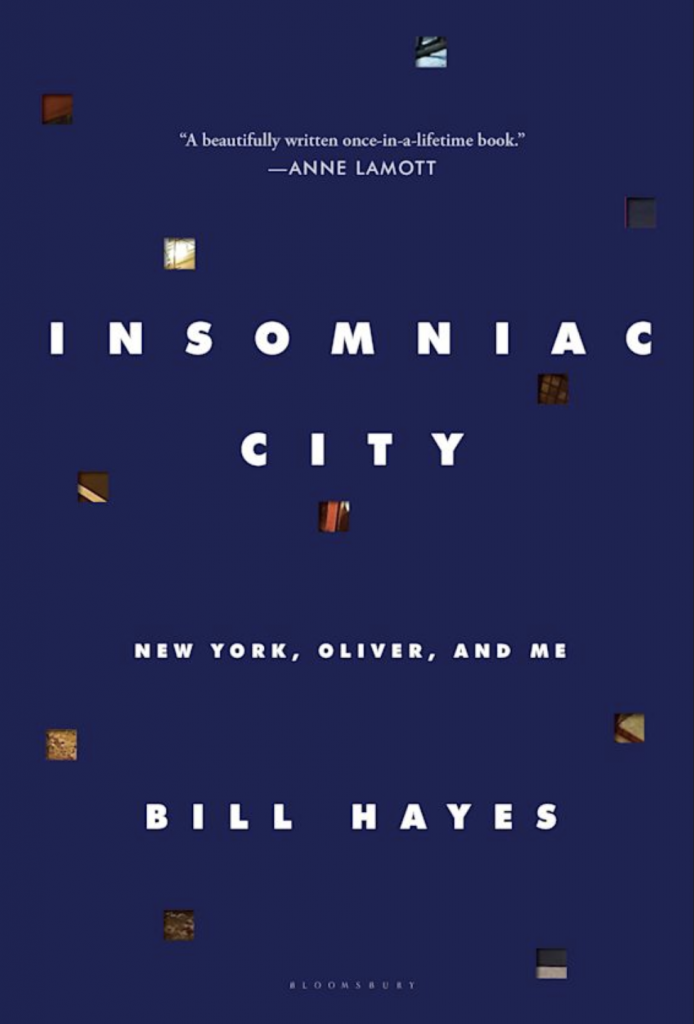

Hayes, B. (2017). Insomniac City: New York, Oliver Sacks, and Me. New York: Bloomsbury.

“I don’t so much fear death as I do wasting life.”

“The most we can do is write – intelligently, creatively, critically, evocatively – about what it is like living in the world at this time.”