Key Quote:

“If you haven’t read hundreds of books, you are functionally illiterate, and you will be incompetent, because your personal experiences alone aren’t broad enough to sustain you” (p. 42). — Jim Mattis

Key Points and Concepts

Leadership Fundamentals: The Three Cs

• Competence: You must master the basics in order to be successful in complicated situations (p. 11).

• Caring: Show your subordinates that you care by being honest with them and trusting them (p. 11).

• Conviction: Don’t make exceptions to the rules. “Know what you will stand for and, more important, what you won’t stand for” (p. 12).

Define the Problem

The first step is to define what problem you are trying to solve. Without a clear objective, you are wasting all of the talent at your disposal (p. 234). “In some cases, I could see what our policymakers didn’t want to happen—we didn’t want Israel attacked, didn’t want Iran with nuclear weapons or mining the Straits of Hormuz, and so on—but I couldn’t find an integrated end state we were trying to achieve: What does it look like when we’re done?” (p. 191).

“Reviewing my self-assigned reading, one fact stood out repeatedly about militaries that successfully transformed to stay at the top of their game: they had all identified and defined to a Jesuit’s level of satisfaction a specific problem they had to solve” (p. 172).

Learn from Reading

Read widely, especially history. You can learn from the mistakes of others so that you don’t make them yourself. “We have been fighting on this planet for ten thousand years; it would be idiotic and unethical to not take advantage of such accumulated experiences. If you haven’t read hundreds of books, you are functionally illiterate, and you will be incompetent, because your personal experiences alone aren’t broad enough to sustain you” (p. 42).

It can inspire you to be creative and realize you have more options than you might think. “Slowly but surely, we learned there was nothing new under the sun: properly informed, we weren’t victims—we could always create options” (p. 12).

Ask your mentors for a list of recommended readings (p. 9).

Having a common reading list can make sure that everyone builds off a base of shared knowledge and understands certain fundamental concepts. This makes complicated discussions easier (pp. 42-43).

Learn from Rehearsal

You only start to feel comfortable in a situation when you have been through it many times and tried multiple potential variations. You shouldn’t ever be doing something for the first time during a critical moment (pp. 150-151).

“I knew that if we kept a Marine alive through his first three firefights, his chances of survival improved. We needed a simulator to train and sharpen cognitive skills until a young leader could swiftly appraise a situation and not hesitate before taking action. He had to develop the cognitive equivalent of muscle memory in order to instinctively seize the initiative” (pp. 150-151).

Learn from Visualizations

There are many examples using visualization (or as Mattis calls it, “imaging”) as a form of communication. It helps the group understand what everyone’s role is and how to create harmony on the battlefield. For certain exercises, they use “a map the size of a basketball court, nicknamed the “BAM”—the Big-Ass Map” (p. 202).

Visualizations can help get your point across to someone who is not as familiar with the situation as you are. “…the Polish Minister of Defense Bogdan Klich flew me in a helicopter from Warsaw to the Baltic so I could see with my own eyes the lack of natural obstacles in his country” (p. 174).

Mastery Leads to Improvisation

Once you have a solid command of the basics and have rehearsed multiple times, you can start to improvise and adapt. “My intent was to rehearse until we could improvise on the battlefield like a jazzman in New Orleans. This required a mastery of the instruments of war, just as a jazz musician masters his musical instrument” (p. 26).

Let Your Team Improvise

It is critical to “delegate decision-making authority or face paralyzing chaos” (p. 48).

Once your subordinates know how to improvise, don’t guide them too closely. Tell them your intention and let them figure out the details of how to execute it themselves. This frees up your time and energy and allows them to take the initiative in situations you never foresaw (p. 44).

“…the Marine Corps demanded that, as young officers, we learn how to convey our intent so that it passed intact through the layers of intermediate leadership to our youngest Marines. For instance, you may say, “We will attack that bridge in order to cut off the enemy’s escape.” The critical information is your intent, summed up in the phrase “in order to.” If a platoon seizes the bridge and cuts off the enemy, the mission is a success. But if the bridge is seized while the enemy continues to escape, the platoon commander will not sit idly on the bridge. Without asking for further orders, he will move to cut off the enemy’s escape. Such aligned independence is based upon a shared understanding of the “why” for the mission. This is key to unleashing audacity” (p. 44).

Don’t impose stringent rules if you want to foster improvisation. Give them the basics and broad principles instead. For example, don’t tell soldiers what they can and cannot wear to the gym. This contradicts your stated value of independent decision-making (p. 179).

Improvisation Requires Trust on Both Sides

You have to have radical trust in your subordinates: “Operations occur at the speed of trust” (p. 156). Trying to give commands for every possibility is pointless. You can never anticipate every element of what your soldiers will face in battle.

You must stand by your subordinates even if they make incorrect decisions, as long as you believe they were doing the best they could with the information they had at the time. “When they make mistakes while doing their best to carry out your intent, stand by them. Examine your coaching and how well you articulate your intent. Remember the bottom line: imbue in them a strong bias for action” (p. 45).

Your subordinates must trust you as well. “Trust. That’s what held us together… Joe knew I had considered every option before deciding he had to pull back” (p. 101).

Share Information

One person can never have a true picture of all the information in a given moment, but it is important for decision-making that as many people have relevant information as possible.

“‘What do I know? Who needs to know? Have I told them?’ I repeated it so often that it appeared on index cards next to the phones in some offices” (p. 200).

Be Decisive

You can’t make a perfect decision every time. But it is better to make fast decisions that are sometimes wrong than slow decisions. This is where you must rely on your extensive background reading and knowledge of the basics to guide your instincts (p. 72).

“A military lawyer asked me a list of questions, one of which caused a stir. ‘General, how much time did you consider before authorizing the strike?’ He knew from the record that the time from when I was awakened until I authorized a strike had been less than thirty seconds. ‘About thirty years,’ I replied. I may have sounded nonchalant or dismissive, but my point was that a thirty-second decision rested upon thirty years of experience and study” (p. 141).

You must make decisions quickly, but it is important to set aside time each week to reflect on the bigger picture and your larger strategic goals (p. 200).

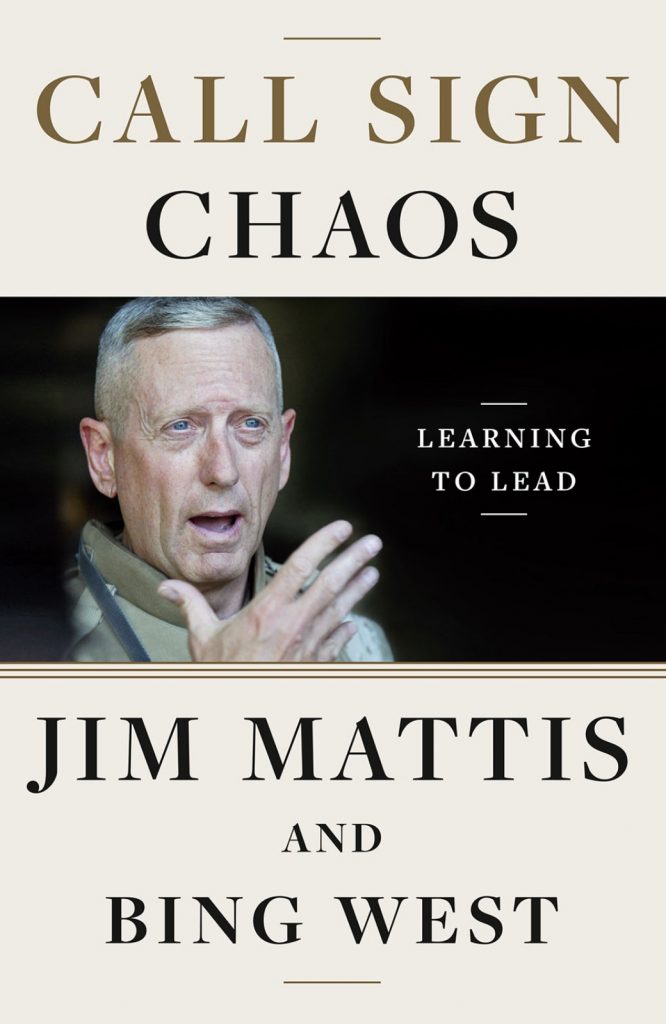

Mattis, J. and West, B. (2019). Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead. New York: Random House Publishing Group.

Read widely, especially history. You can learn from the mistakes of others so that you don’t make them yourself. “We have been fighting on this planet for ten thousand years; it would be idiotic and unethical to not take advantage of such accumulated experiences.

Once your subordinates know how to improvise, don’t guide them too closely. Tell them your intention and let them figure out the details of how to execute it themselves. This frees up your time and energy and allows them to take the initiative in situations you never foresaw.

You can’t make a perfect decision every time. But it is better to make fast decisions that are sometimes wrong than slow decisions. This is where you must rely on your extensive background reading and knowledge of the basics to guide your instincts.