Key Quote

“Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire. Likewise with randomness, uncertainty, chaos: you want to use them, not hide from them” (p. 3). — Nassim Taleb

Key Concepts

The Antifragile: An Introduction. The opposite of the term “fragile” is not “robust” but, instead, “antifragile.” The antifragile person (or system or company or society, etc) doesn’t just survive under stress or attack, as the robust does – the antifragile are “reborn” and made better. “Intellectuals tend to focus on negative responses from randomness (fragility) rather than the positive ones (antifragility)” (p. 41). But the ancients (and everyone’s great grandmother) understood that trouble builds strength and

character, and this is true in all domains. And sometimes we must “fail [so that] others succeed” (p. 45).

Modernity and the Denial of Antifragility. Removing all volatility from systems harms them and eventually causes worsening volatility. A little volatility, risk, variation, trouble, or confusion counters the “adverse affect of [too much] stability,” and too much stability leads to fragility (p. 101). The drive to always intervene and remove trouble – to “do something” – can actually make things worse.

It is most effective to build a system that can handle stressors rather than focusing all efforts on

reducing or eliminating stressors.

A Nonpredictive View of the World. In life, avoid the middle approach of having all your eggs in the basket of low-risk activities. Instead, reduce the downside – “protect yourself from extreme harm” – while taking on a small amount of aggressive risk. This overall approach has a limited downside and maximizes the upside. It prevents you from total disaster and also from fragility. It allows for people to play with fire “and learn from injuries, for the sake of their own future safety” (p. 162, 163).

Optionality, Technology, and the Intelligence of Antifragility. Embrace the new information you receive, the process of trial and error, and the concept of keeping your options open. Do not get locked on a rigid path or goal. Don’t miss simple solutions in search of complicated ones; don’t let rationalism prevent you from innovation and “tinkering” to get the results you want. Don’t overly rely on the role of rationalism in innovation and discovery.

The Nonlinear and the Nonlinear. “For the fragile, the cumulative effect of small shocks is smaller than the effect of an equivalent single large shock.” However, “for the antifragile, shocks bring more benefits (equivalently less harm) as their intensity increases (up to a point)” (p. 271).

Via Negativa (The Negative Way). Failure can be more informative than success. And we need to value what can know by understanding what is wrong as well as what is right. In fact, we often gain greater understanding by cataloguing what something is not more than we do by cataloguing what something is.

The Ethics of Fragility and Antifragility. We must recapture the ethic found in traditional societies who have survived, which is respect for heroism and sacrifice. We must valorize the ones – whether soldier or saint – who willingly take on risk and downsides for the sake of others. People who take

on risk have “skin in the game.”

Thank You, Stressors & Errors

“Since the opposite of positive is negative, not neutral, the opposite of positive fragility should be negative fragility (hence [the] appellation of

“antifragility”).” Neutrality “conveys robustness, strength, and unbreakability” (p. 32). But the

antifragile concept conveys rebirth and growth

beyond merely surviving.

Stressors and errors are sources of information.

Every trial and error provides information on what does not work and helps to pinpoint the solution (p. 71).

“Had the Titanic not had that famous accident, as fatal as it was, we would have kept building larger and larger ocean liners and the next disaster would have been even more tragic” (p. 72).

Under-compensation is what develops out of the absence of stressors or challenges, and this degrades even the best of the best. “It is said that the best horses lose when they compete with slower ones, and win against better rivals” (p. 43).

Invention, however, comes out of need or difficulty. A system that overcompensates responds to information about a possible stressor by building extra capacity and strength in anticipation of the worst outcome. Even in the absence of a stressor, redundancy of extra strength is an investment opportunity rather than an inefficient, defensive insurance mechanism (p. 45).

Antifragility is, therefore, that which overcompensates to stressors and damage (p. 48).

Manufactured Stability – The Antithesis of Antifragility

Man-made “smoothing” of randomness produces the illusion of stability while naïvely “fragilizing”

the system – and preventing its antifragility – in an effort to protect it (p. 85).

In contrast, variability and randomness produce the illusion of greater risk but yield antifragility.

Variability provides sources of information concerning the environment, which result in greater

optionality and antifragility (p. 85).

“How Not to Be a Turkey.” A turkey is fed every day for a thousand days, with no variability, until a few days before Thanksgiving. The soothing predictability of life as a turkey leading up to Thanksgiving confirms a critical mistake that turkeys often make: mistaking the absence of evidence of harm for evidence of absence. Not being a turkey starts with determining the difference between true stability and manufactured stability (p. 93).

Artificially suppressing volatility makes the system extremely fragile, because there are no visible risks (p. 106). Variations act as purges, allowing hidden vulnerabilities to come to the surface (p. 101).

The concept of iatrogenics is the idea of receiving greater harm from treatment than benefits (p. 111). Over-intervention (“naïve intervention”) causes long-term harm. Systems are naturally antifragile, but when we “fragilize” them by intervening too much, we weaken them in the long run (p. 119).

“Noise vs. Signal.” Noise is what you are supposed to ignore, whereas signal is what you need

to heed (p.125). We need to learn to be strategic not neurotic in handling challenges.

The more frequently you look at data, the more “noise” you are disproportionally likely to get, rather than the valuable information – the signal. The best way to mitigate interventionism is to ration the supply of information as naturalistically as possible (p. 126).

Fragility Vs. Antifragility

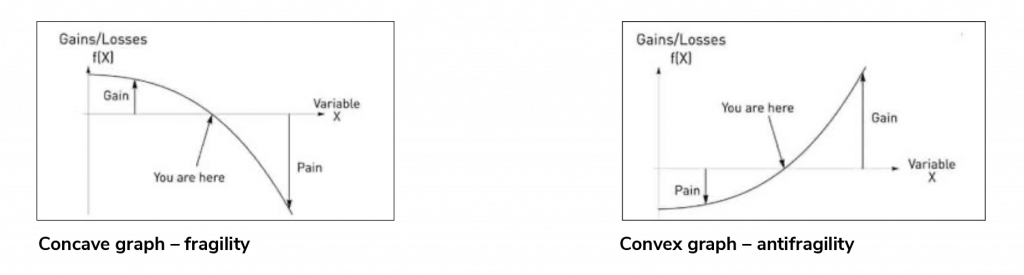

Concave curve: For the fragile, shocks bring higher harm as their intensity increases (p. 268).

On a gain/loss curve, fragility is concave – the cumulative effect of small shocks is smaller than the effect of an equivalent single large shock (pp. 168-171). One illustration of the concept: it is better

for the fragile to be hit with a thousand small pebbles than one 50-pound boulder.

Convex curve: For the antifragile, shocks bring more benefit as their intensity increases (to a point) (p. 271).

Antifragility is convex and thrives from volatility (pp. 171-172).

One illustration is that of the weightlifter (antifragile) developing muscle strength. In his case, increasing weight produces disproportionate gain. “The very idea of exercise is to gain from antifragility to workout stressors,” and, in fact, “all kinds of exercise are just exploitations of convexity effects” (p. 278).

Optionality – The Philosopher’s Stone

The antifragile value optionality – which is limiting their downside while maximizing the possibilities of the upside. One illustration of the concept is that of the rent-controlled apartment dweller vs. the landlord. If rents go up, the dweller is not harmed. If rents go down, the dweller can move to a less expensive dwelling, and the landlord is harmed. The renter has minimized his downside and maximized his upside – he has optionality.

“The Philosopher’s Stone.” If we have optionality, we don’t necessarily need to be right or have intelligence. We just need the wisdom to not do unintelligent things to hurt ourselves and to recognize favorable outcomes when they occur (p. 180). The fragile lack options in the first place. The antifragile need only to select the best option (p. 183).

Achieving Antifragility – Stoicism & Seneca’s Barbell

Stoicism, a philosophy ascribed to philosopher

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, promotes antifragility

through achieving a state of immunity from external circumstances and, particularly, from fate (p. 153).

Physical and emotional dependence on circumstances and possessions introduces a negative

asymmetry – where there is a lot to lose and a little to gain – which results in fragility (p. 154).

Seneca countered fragility and divorced himself from the adverse effects of fate by relinquishing his dependence on material possessions. He suggested writing off possessions as a way to achieve freedom from the negative effects of circumstance and volatility. By choosing limited harm, Seneca lost nothing (nihil perditi) from adverse events and regained a sense of control over fate (p. 155).

As the “domestication, not necessarily the elimination, of emotions,” Stoicism is the positioning

necessary to reduce psychological fragility and “the sting of harm” (p. 156).

The concept of positive asymmetry – where there is a little to lose and a lot to gain – is called Seneca’s barbell. It represents a dual attitude towards playing it safe in some areas and taking a lot of small risks in other areas to achieve antifragility (161).

Antifragility takes hold of this positive asymmetry using “the combination aggressiveness plus paranoia – clip your downside, protect yourself from extreme harm, and let the upside, the positive Black Swans, take care of itself” (pp. 161-162).

One illustration of this positive asymmetry is a financial one: “If you put 90 percent of your funds in boring cash” and at the same time “10 percent in very risky, maximally risky, securities, you cannot possibly lose more than 10 percent, while you are exposed to a massive upside” (p. 161).

Like Stoicism, “the barbell is a domestication, not an elimination, of uncertainty” (p. 167).

Achieving Antifragility – Via Negativa

Via Negativa – the negative way – is an approach used by professionals to describe learning truth from the negative. We learn from what something is not, from what does not work, from what is wrong vs. what is right (p. 301).

Pros understand this principle. For example, “chess grandmasters usually win by not losing; people become rich by not going bust (particularly when others do); religions are mostly about interdicts;

the learning of life is about what to avoid” (p. 302).

Negative knowledge (what is wrong, what does not work) is more robust to error than positive knowledge (p. 303). Failure is much more informative, and therefore more robust, than success

or confirmation (p. 304).

“The good is mostly in the absence of the bad” – Ennius (p. 360)

Taleb, N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder, Random House.

Removing all volatility from systems harms them and eventually causes worsening volatility. A little volatility, risk, variation, trouble, or confusion counters the “adverse affect of [too much] stability,” and too much stability leads to fragility.